From Counterfeit Sámi Dresses to Global Warming – Intellectual Property Right as a Tool to Protect Indigenous Knowledge and Culture

Lapland is probably the most exotic region in Finland, attracting hundreds of thousands of visitors every year from all parts of the world. You have probably come across with marketing material or commercials that advertise Finnish Lapland with a person wearing exotic-looking, bright-colored costumes, or ran into blue or red colored four-pointed hats with embroidered ribbon details. You most likely know that these garments and headgears originate from the indigenous Sámi culture. However, have you ever considered that this kind of cultural products might be considered as intellectual property?

Intellectual property rights and the rights of indigenous peoples are not often discussed together. However, there lies plenty of issues in the interface of these two topics. In December 5th 2016, University of Lapland (IP lecturer Dr. Rosa Maria Ballardini being the primus motor) hosted a seminar “Indigenous Knowledge, IPRs and Human Rights”. The seminar aimed at delving into the key research questions related to the intersection between indigenous peoples’ knowledge, intellectual property rights and human rights. Targeted for the readers of IPR info, this article focuses on the intellectual property questions that were discussed in the seminar.

Santa Claus does not exist, Sámi people do

The seminar was opened by the Dean of the University of Lapland Faculty of Law, Professor Juha Karhu, who gave a brief, yet inspiring introduction to the topic of the seminar. Dr. Karhu pointed out to the students, researchers and other listeners that rights in their traditional knowledge are a part of the Sámi cultural rights, which originate from the United Nations Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples article 31. The article guarantees the indigenous people the right to maintain, control, protect and develop their cultural heritage, traditional knowledge and traditional cultural expressions. In other words, not everyone is entitled to the traditional knowledge of the indigenous people, nor are the indigenous people bound to disclose that information.

The Sámi people´s right to their own culture includes the right to keep their culture to themselves. However, the Sámi culture’s elements are used in various contexts without the source culture’s consent, tourism being one of the most visible examples. Furthermore, the source culture is not receiving any kind of compensation for the this. One example of this kind of cultural appropriation is a counterfeit Sámi outfit, which is often used by tourism companies, but disapproved by the Sámi people. When you take a look at Finnish souvenir shops, the Sámi dress and hat appear to be in public domain and free for everyone to use, almost like the character of Santa Claus.

Intellectual property protection starts from environment protection

The keynote speaker of the day was Dr. Matthew Rimmer, who travelled to Lapland all the way from Austaralia. Being the Professor of Intellectual and Innovation Law in Queensland University of Technology, Dr. Rimmer is one of the world’s leading experts when it comes to the intellectual property issues of the indigenous knowledge, culture and heritage.

During Dr. Rimmer’s speech, it became quite clear that the intellectual property rights – or any rights – of the indigenous people cannot be discussed without mentioning the climate change. Global warming threatens the whole existence of the indigenous cultures worldwide. Thus, it is important to take into account the indigenous rights when measures against the climate change are being agreed on in a global level.

As a conclusion, the protection of the indigenous knowledge and culture should start from the protection of the environment they live in. This is the only way to ensure that the indigenous knowledge, traditions, culture and heritage can be maintained, developed and protected. Lately the question of the protection of indigenous people has emerged during international discussions concerning intellectual property, the environment, and climate change. The Paris Agreement 2015 provides some limited recognition of indigenous knowledge – but not full acknowledgment of Indigenous Intellectual Property.

Copyright to Sámi dress and other cultural products?

As stated previously, the use of fake Sámi dresses is one of the most visible form of cultural appropriation in Finland. However, when it comes to traditional wear as intellectual property, the issue is not that simple. First of all, in many jurisdictions clothing and accessories have traditionally been seen as useful articles or “applied art” and thus, not entitled to copyright protection for example. When it comes to the Sámi dress and other indigenous wearables, there is also the problem that that this kind of cultural products are often born “accidentally” or evolved during a long period of time, and that there is no single author. What makes communal authorship difficult is that it is difficult for unidentified authorship to meet the standards of intellectual property law. Creative expressions of unincorporated groups, such as particular race, ethnicity, religion or profession, are more likely to fall outside of the realm of intellectual property and might be considered legally invisible (Scafidi, 2005).

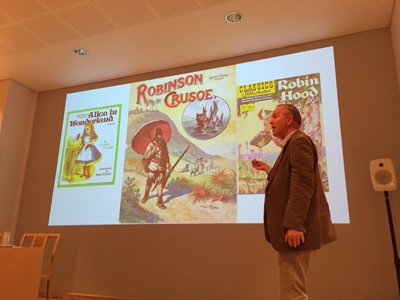

However, when the Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Article 31 is viewed from the intellectual property perspective, granting of exclusive rights to indigenous cultural products seems to be inevitable. The widespread use of counterfeit Sámi products is mutilating the public image of the Sámi people and depriving the cultural value of the original products. Dr. Karhu brought up that in 1967, the Finnish Supreme Court held in its decision KKO 1967-II-10 that publishing of shortened versions of classic novels such as Alice in Wonderland, Heidi and Robin Hood was breaching the Finnish Copyright Act section 53 which prohibits the public treatment of a literary or artistic work is “in a manner which violates cultural interests, notwithstanding that the copyright therein is no longer in force, or that copyright has never existed”. The shortened versions in question were written in poor language and essential parts of them were left out, which lead the Supreme Court to consider them as violations of cultural interests.

The legal thinking in KKO 1967-II-10 in could be adapted to the unauthorized use of the Sámi dress, hat or other Sámi products. This way, the counterfeit Sámi products could be considered as violations of the Sámi cultural interests. Thus, the Copyright Act 53 § would provide the Sámi people one solution to the question about the exclusive right to their traditional apparel, accessories and other products.

In addition to copyright protection, development of a community-oriented certification of authenticity could be one option that could help the indigenous people to reserve an exclusive right to their cultural products. According to PhD candidate Piia Nuorgam, there has been an attempt for this in the 1980s when the Sámi agreed on a common trademark, Sámi Duodji, but this certification has not met the expectations set for it.

Counterfeit Sámi products as harassment

In addition to intellectual property, there is another perspective from which an exclusive right to indigenous cultural products such as the Sámi dress could be granted. PhD student Piia Nuorgam from University of Lapland presented a fresh approach to the subject. Nuorgam is researching the wider use of the Sámi dress as a potential breach of the Finnish Non-Discrimination Act. The act is meant to apply to activities which are not directed to some person directly but to a certain group, whereby it also protects a group’s dignity. For example, joking in way that humiliates an entire population can offend a person, even though this was not the intention. Fake versions of the dress are sold not only as souvenirs but also as costumes for fancy dress parties, which can be considered as joking about the Sámi population.

Nuorgam pointed out that the inappropriate use of the Sámi dress diminishes the Sámi culture and has an impact on the public Sámi image, boosting the stereotypes of the Sámi people. Protection of the Sámi dress is also protection of the dignity of the Sámi people. Also the Finnish Non-Discrimination Ombudsman has brought up that the demeaning use of Saami dress may be viewed as harassment, which is a form of discrimination.

In conclusion, the discrimination perspective and intellectual property perspective can complete each other when measures of protecting of indigenous knowledge and culture are being considered.

Improvement instead of ignorance

When it comes to intellectual property rights, indigenous knowledge, traditions and products are often ignored. Instead of ignoring the intellectual knowledge of the indigenous people, we should improve of its protection. However, one specific concern rose among the speakers of the seminar: what effect does the new president of the United States have on the rights of the indigenous people worldwide? Since Mr. Trump is not particularly famous for respecting minorities, improving of the intellectual property protection of the indigenous knowledge in the global level might face some challenges in the near future. Despite of that, the topic is clearly getting more and more attention among the world of intellectual property research, which is a delightful development trend.

Heidi Härkönen

Doctoral Candidate, University of Lapland

President of the Finnish Fashion Law Association

Susan Scafidi (2005) Who owns culture?: appropriation and authenticity in American law.

In Finnish:

Kuvaohjeistus: saamelaisuuden ja saamelaiskulttuurin esittämisen periaatteet (Saamelaiskäräjät, 2016)